Newsletter of the Department of Religious Studies at Southwest Missouri State University

By Joby Taylor

In 1956 the anthropologist Horace Miner composed his now famous essay “Body Rituals of of the Nacirema,” describing the elaborate superstitions of a thriving North American tribe.

Those who are familiar with the article will recall these people’s obsession with dental hygiene, their enormous monetary support of healers, and their shame-laden body image. Miner’s hook is baited; ”Nacirema'” is of course, a thinly veiled inversion of “American.”

The essay makes a simple but important point: they (the observed) are we (the observers). When I assigned this as a reading in my Religion 100 class last semester, only 2 of 40 students failed to bite; the rest waxed eloquently on the horrors of such “primitive” living—and yes, I too must admit a similar embarrassment when I first read the essay. Miner’s point is well taken; from any vantage point other than our own, would we recognize ourselves?

“Know thyself’ goes the ancient Greek dictum, or, as the Chicago scholar of religion Jonathan Z. Smith urges, “the student of religion must be relentlessly self-conscious.” The best method I have found to practice such self-scrutiny is a program of frequent cultural estrangement (even if this requires enjoying, incidentally, some beautiful tropical paradise, or so my rationalization goes).

In need of a jolt, I find no substitute for literally throwing myself lock, stock, and barrel into some other geographical world, in the midst of something foreign enough to shake my constantly adjusting worldview.

All this is to say that I have spent my past two summers wonderfully estranged by working on the island of Guadeloupe. Located in the French West Indies near the islands of Martinique and Dominica, Guadeloupe’s history since Columbus’ landing shares the turbulent, sometimes tragic, story of many of the Caribbean isles.

None of its earlier inhabitants survive, and the current population is an intermingling of the descendants of French colonials, former slaves taken principally from West Africa, and East Indian plantation workers.

To their language, French Creole, consider adding vocabulary drawn from such languages as Spanish, Dutch, and Portuguese and you begin to understand the cultural complexity of this small comer of the earth, a corner that, to my mind at least, did not exist until just two years ago.

Today, Guadeloupe is an official Department of France (more like Hawaii than Puerto Rico). This, most importantly, translates into fresh baguettes and pastries every morning, wines and cheeses of all descriptions imported even to the smallest of towns, and a haut couture twist to island fashions.

The island exports sugar and bananas from its plantations, and produces rum as its principal sources of revenue. Tourism comes in a close third, which contrasts with most Caribbean locales where tourism is a hands down first. Nonetheless, metropolitan France must continue to subsidize the island economy.

Roman Catholicism is the predominant religious tradition on the island, although, in an interesting Springfield connection, the Assembly of God community is fairly large and apparently growing. I also encountered Mormons and Jehovah’s Witness.

Remarkably, there is little visible sign of anything resembling traditional African practice. Understandably perhaps, Guadeloupeans of color (Indians and Africans) seem to have an ongoing, if mild, love/hate relationship with their colonial mother, France.

In full knowledge of the need for subsidy, small factions toy with calls for political independence but never gain a serious audience. 1998’s celebration of the 150th anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Guadeloupe was met with solemn parades and memorials, not angry protests.

I sensed on the island an aura of discontent with economic dependency, but a strong multicultural sense of identity. Furthermore, their level of racial intermarriage leaves U.S. demographics looking more like a checkerboard than a melting pot.

Guadeloupe offered a rich environment within which to find myself asked to situate a summer program for VISIONS International, an organization that provides American high-school students with cross-cultural community service opportunities.

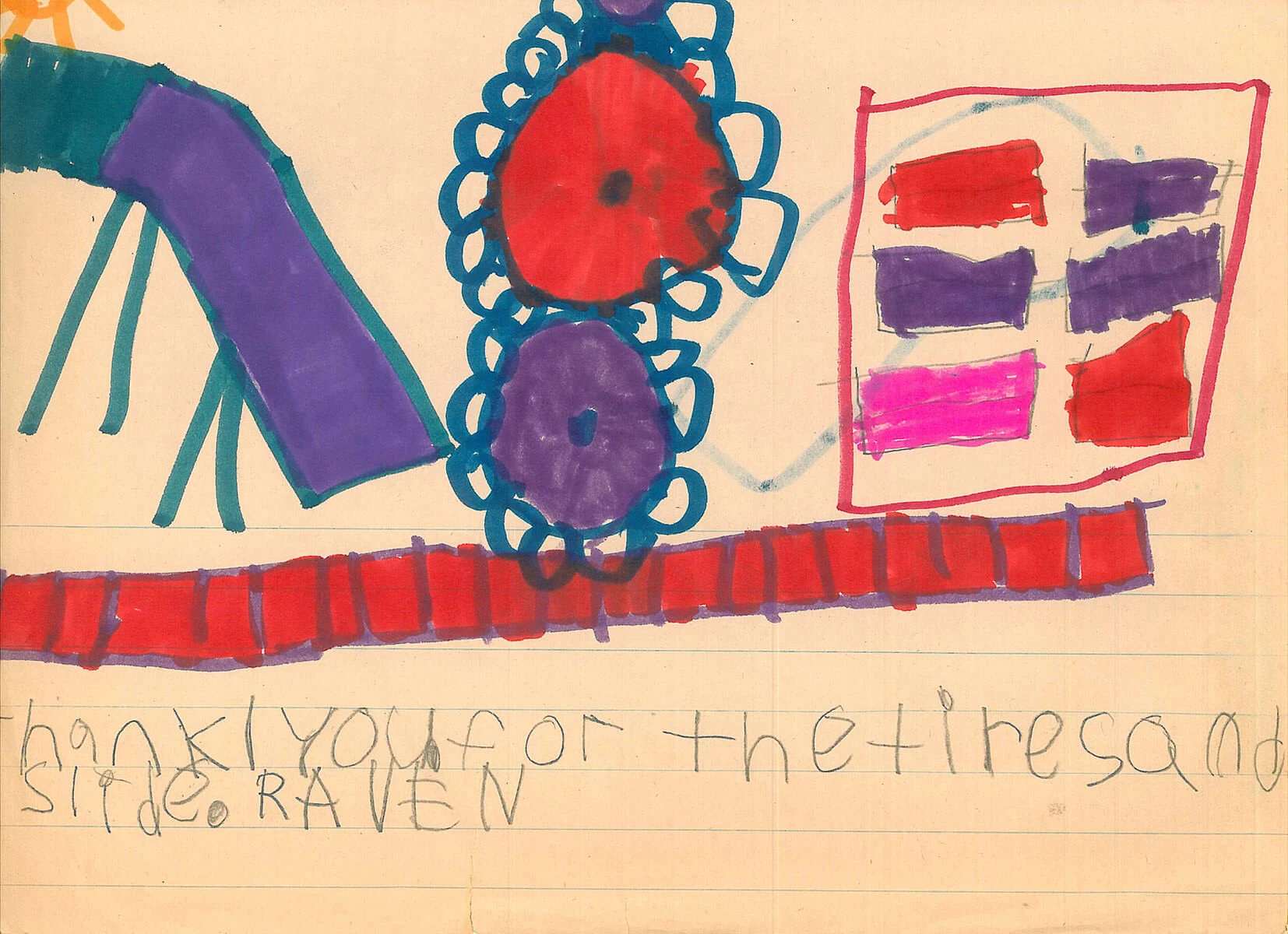

With the aid of 5 staff members (two American, one Guadeloupean, and two French) we attempted to steer 25 adolescents through the months of June and July as participants, not tourists, in the small coastal community of Trois Rivieres. Hearkening often to my initial months as a Peace Corps Volunteer our goal was to provide these kids with a safe opportunity to broaden their world, and to take as their admission ticket to the island a spirit of voluntary service.

The Guadeloupean center for youth and culture, under the direction of Pierrette Cairo, invited us into their community and sketched the work and recreational program, choosing their own youth group of 25 local students to act as our counterparts.

On the work site (each Mon.-Fri from 8 am-2 pm) we together established a community park, clearing trash, building benches and picnic tables, planting trees and shrubs, and painting murals on the surrounding walls of the public swimming pool. It was not all work of course, and Pierrette and her gang showed us quite a time.

Over the course of the summer we climbed to the top of a steaming volcano, swam in the basin of a 350 foot waterfall, scuba dived at one of Jacques Cousteau’s personal favorite reefs, danced in an all-night Carnival celebration, and of course made a serious attempt at trying to spend an afternoon on nearly every beach in Guadeloupe.

It was with tears that our American kids left their newly formed friends to return home. Perhaps they are different than before the summer began. Perhaps they understand themselves better because of their experience of cultural contrast. Perhaps they now see their worldview as a work in progress. For myself, I know that these are all true.