As another summer community service season on the Northern Cheyenne reservation draws near, we found this in our archives of staff and student volunteer writings. Haviland Staggers spent many seasons directing VISIONS summer programs in Montana. She wrote the following reflective piece when she was in graduate school completing her Masters in Education.

CHEYENNE SUMMERS

In May 1992 I graduated from college and became, suddenly, an adult with a fuzzy plan to move to Missoula, Montana. Before the actual move to Missoula, I accepted a job that would take me to the Northern Cheyenne Reservation where, with a group of teen volunteers, I would help build a playground and do other community service projects. My employer was a relatively newly established organization called VISIONS.

After staff training in Pennsylvania in mid-June, all the Montana staff piled into three 15-passenger vans and headed west to the St. Xavier Indian School on the Crow Indian Reservation in Montana. We drove straight through for two days until we landed on the reservation. After a poor night’s sleep, two staff teams continued farther west with the vans. (There were four teams of six staff each destined for four different Montana reservations.) The other two teams stayed behind, one on the Crow, the other to work on the Northern Cheyenne. We leased small buses for both programs from the Crow tribe.

I should underscore a historical point here. The Crow and Northern Cheyenne reservations share a common boundary, but not necessarily friendship. When the US government confined the native peoples of Montana to reservations, it made a calculated decision to let traditional enemies continue fighting each other. The Cheyenne and the Crow tribes were traditional enemies. Centuries-old memories of warfare have not faded over time.

When the Northern Cheyenne summer staff team rolled onto the reservation in those bright yellow mini-buses with “Crow Head Start Program” emblazoned on the sides, we were not, shall we say, inconspicuous. Our first stop was Lame Deer to meet our primary contact and liaison, Florence Running Wolf, head of Cheyenne Children Services, who looked rather stunned when six bleary-eyed, bed-headed, very white, 20-somethings spilled out of the Crow Head Start bus. After a few seconds of staring and deep breaths Florence invited us to lunch.

At the time, I felt that I was pretty well equipped for the experience that lay ahead on the reservation. I had worked with teenagers before. And, I had studied Indians in college. I felt their plight. I was politically, correctly indignant on their behalf. My history major in college was concentrated in the Trans-Mississippi West, specifically, Indian / Settler relations on the Plains. I liked to joke that I did my junior year abroad…in Missoula, Montana at the University. Missoula is hardly foreign, but the line got a laugh, so I kept using it…until the moment I first stared down the main street of Lame Deer. I was in another country.

After our lunch with Florence, we piled back into the bus and drove to Birney Village at the southernmost edge of the reservation, our home base for the summer. As we cleared the final rise in the road and looked out over the endless valley to the south all we saw were aged massive cottonwood trees everywhere and all along the Tongue River, the border between the reservation and the modern world. The little village was lost to our unpracticed eyes until we were in its very midst, on the oldest portion of the reservation, populated with log cabin shacks and houses of varying habitability. There were no stores, no gas stations, no “business” enterprise of any kind. This was my home for the summer.

“Don’t drink the water from the taps, even to brush your teeth. Use bleach in the rinse water with your dishes,” said Mike Running Wolf, Florence’s husband, when we caught up with him at the tiny de-consecrated Catholic Church that was to be our home for two months. “And don’t investigate those empty cabins. Tell your kids. That’s important if you are going to live in this village.”

Mike was the storybook image of an Indian with his long black braids, pearly teeth, regal face and finely chiseled features (except for the cigarette clinging to his lip; he’s since quit smoking.) If I squinted I could overlook the green Adidas running shorts and orange, black and gold striped tank top. I was a product of ivory tower education. I wanted the archetype, and so was taken aback by the reality.

The cabin shacks, I learned, were remains of the first houses on the reservation, deserted when the last of a line died or was married off. They are testaments to the past, to a people forced to settle and farm even as their souls ached to soar over the Plains. As for the water, well, we had to buy a lot more coolers that first summer. The freshwater spring used by the village was seven miles back toward Lame Deer. The water flowed steadily from a pipe wedged into the hillside just off the road. Most remarkable were the small fabric bundles and un-opened packs of unfiltered Marlboros suspended by strings from the branches around the pipe, gifts left to honor the Spirit who provides this fresh water.

For eight summers I returned to the Northern Cheyenne reservation with VISIONS. In those years I was, to paraphrase Steinbeck, “having a love affair with Montana;” actually, it was a love affair with the forgotten southeastern corner of Montana. My work boots, my second pair of Danner Lights, looked like elf shoes with their upturned tips. The cracked leather spoke of many hours in the dry Montana summer. I happily worked the post-holer and digging iron, hacked up a rattlesnake at the urgent behest of several older Cheyenne women, and convinced a fire fighter friend to teach me to use his Husqvarna. I was sore, dirt-smeared and always one day past needing a shower. But I felt so beautiful and tall, and I was learning, touching some of that history I had loved in the pages of my texts.

I made many mistakes when I first arrived. I wanted so badly to belong. The people chose to care about me despite my naïveté. It took me several years to settle down in my own skin, to see the people and not the myth. Mike and Florence Running Wolf loved me enough to tell me the history I so much wanted to embrace, while balancing my diet with berry pudding, boiled beef, Shake n’ Bake Chicken and satellite TV. They invited me into the sweat lodge, Cheyenne woman-style. They took me to a Sun Dance in the hills beyond Busby where Mike solemnly asked if I was menstruating, and, if so, told the ramifications of my “strength” if I were to get too close to one of the dancers. Then, completely uncharacteristically, Mike unbuttoned his shirt and rather academically inventoried the scars from his own Lakota Sun Dance twenty-five years before.

My summers on the Cheyenne awakened a sense of the spirit within and without me. Before then, the soul-capturing moments that served to define my belief system had taken place in the quiet, or violence, of the natural world: the ethereal pink alpine glow reflecting off Franconia Ridge, the undulating blanket of the Northern Lights while camping far from civilization in the Cloud Peak Wilderness, hurtling down the Valley Way Trail encased in fog and whipping branches, breathing what must have been chlorophyll itself as I tried to outrun Hurricane Bob. People had never figured into this spiritual equation before.

Mike and Florence, her many sisters and brothers-in-law, and the village of Birney embraced me as family. And what a family it is. Florence is directly descended from Chief Black Kettle who was killed along with many of his people in the Sand Creek Massacre in 1864. Her sister, Rachel Magpie, is a noted storyteller, admired bead worker, and rancher. Another sister, Charlotte, married a spiritual leader and struggled at first to find her own way as a Native woman in a difficult marriage to a powerful man. Elmer Fighting Bear—who, when he wore his traditional dancing clothes complete with mirrored sunglasses and black jumpsuit, always made me think of Elvis—was the Keeper of the Sacred Medicine Hat. The Medicine Hat is one of the two most important and potent of Cheyenne symbols. The Northern portion of the tribe cares for the Medicine Hat and the Southern Cheyenne band protects the Arrow Bundle; together they symbolize the unity of the whole Cheyenne tribe despite the two bands’ physical distance today. I marvel still that I drank Kool-Aid with the Keeper of the Hat.

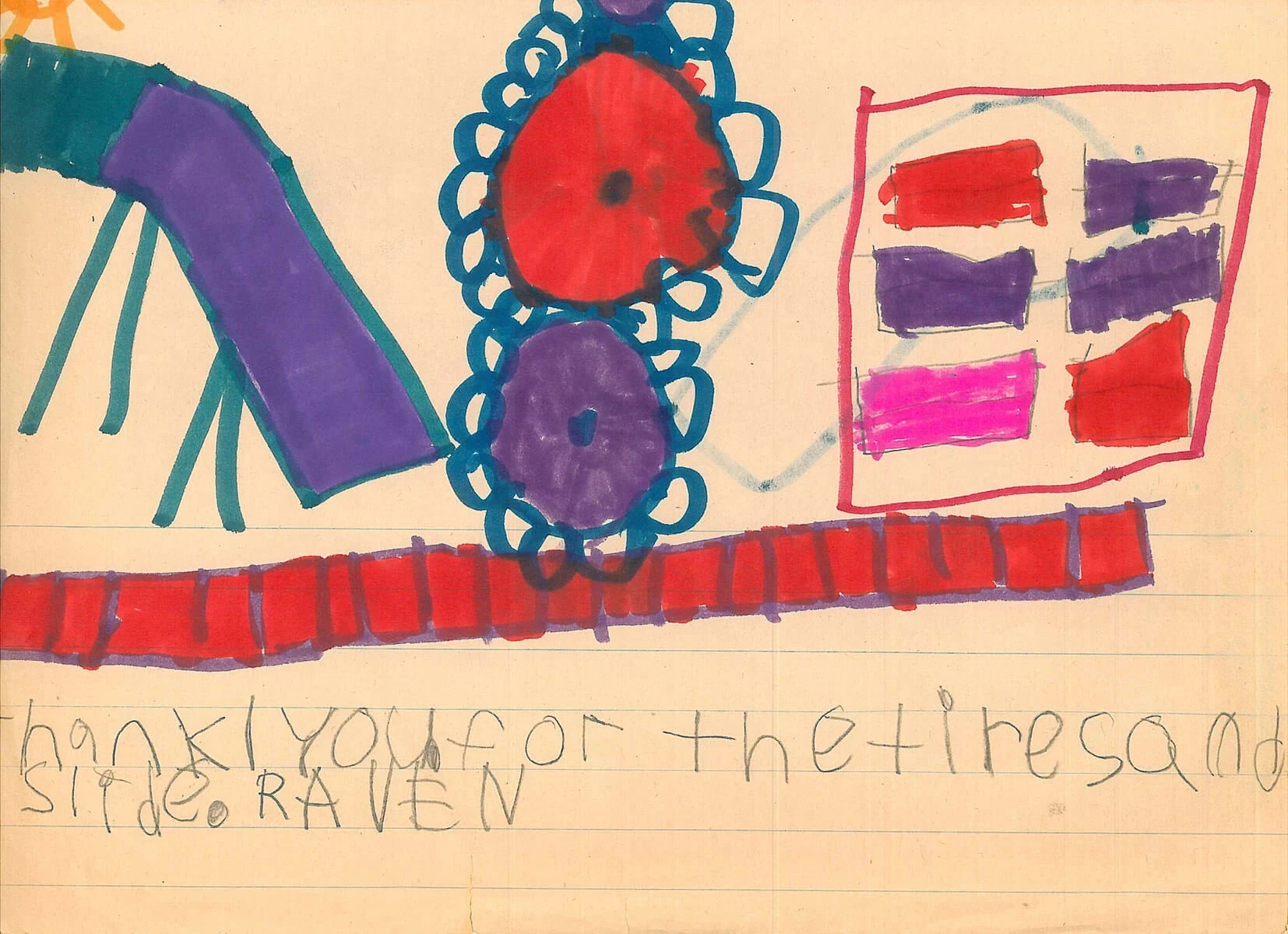

When my seasons on the Northern Cheyenne finally came to an end, I had fallen briefly in love with a young Cheyenne man. I had gotten a tattoo of the Cheyenne Morning Star on my left shoulder. I had been named “Little Sister” by Birney Village elders and presented with an Eagle Feather blessed by Elmer Fighting Bear. With VISIONS participants, I had built five playgrounds, three pow-wow arbors, fenced a baseball field, built and painted a free-standing wooden library, and made deep friendships.

I had not, however, become Cheyenne, nor would I ever be Cheyenne. I came to understand and be at peace with this, while carrying forever the treasures of my time on the Northern Cheyenne.

––Haviland Staggers, VISIONS staff member and program director 1992 – 1998, 2001