By Owen Clarke

One of the highlights of our Montana Farm & Ranch Program is working with Barney Creek Livestock, a regenerative grazing operation run by Meagan and Pete Lannan and their two young children, Maloi (15) and Liam (13).

“We grow grass, lease that grass and raise grass-fed beef,” Meagan said. In doing so, they contribute to creating carbon sinks, which draw down and trap carbon emissions. They also restore grassland ecosystems, providing healthy, untrammeled lives for cattle in the process, and harvest nutrient-rich meat to boot. All told, their work aims to holistically regenerate the land.

A fourth-generation agricultural family, Meagan and Pete lease the land on which they farm, the Jordan Ranch, from Pete’s father, who bought it from his father, who bought it from his father. The land has been in their family since 1900, when their ancestors purchased the ranch from the estate of Barney Maguire, who homesteaded the site way back in 1867.

So, it’s safe to say that, like many of the outfits VISIONS partners with, Barney Creek and the Lannans have deep roots here in the Paradise Valley.

Cows as a Workforce

Okay, so the cows aren’t clocking in for a 9-5 in suits and ties. But they do play a crucial role in the regenerative agricultural processes at Barney Creek. They’re an irreplaceable part of the ecosystem.

The “mob mentality” cattle use when grazing means they eat both weeds and desirable plant growth. They trample vegetation, “armoring” the soil by pushing that vegetation back into the soil. This prevents erosion and facilitates moisture retention, among other things.

“We use cows as a workforce, to graze and help people bring back their land,” Meagan said.

The Barney Creek approach isn’t just about cows, though. It centers around a holistic, ground-up approach, beginning with the soil. Healthy, nutrient-rich soil leads to healthy and diverse plant life. Healthy plants create food for healthy cows. This year Barney Creek only had to feed hay to their cattle 140 days out of the year (some other farms feed hay for well over half the year). The rest of the time the cattle grazed the land.

Healthy plants go hand-in-hand with healthy soil, too. This is because, among other factors, when a plant is grazed, it sluffs roots to feed soil biology, building organic matter, which helps the soil hold moisture.

Finally, these healthy cows lead to healthy people (for those that choose to consume the meat from the cows that are harvested). “Our model of agriculture comes first,” Meagan said. “The by-product of that is selling grass-fed, direct-to-consumer beef.”

Meagan believes it’s extremely important to recognize the critical role that animals play in the grass ecosystem. “Making cows the enemy, charging that divisive conversation of plants vs. animals… It’s not the answer,” she said.

Through their grazing operation, they hope to educate the farmers they work with on this topic and more. “We teach the landowners we work with about soil health, plant tissue tests, water tests and what the cows are doing. We take them out in the pasture, we show them dung beetles and tell them why they’re important. We help them understand how to create a holistic, regenerative system.”

It’s All About Management

Many VISIONS participants will hear Meagan quip, “It’s not the cow, it’s the how.” She didn’t create the slogan, but it’s one of her favorites.

What it means is that the system is what’s important. It’s not the individual components of the system (the cows, the grass, the soil, etc.). It’s how each of those components interact and are managed.

The #1 word in regenerative agriculture is ‘context,’ according to Meagan. Context means the land is managed using a variety of interconnected regenerative agricultural principles, including maintaining a living root, minimizing soil disturbance, maximizing crop diversity (easy for Barney Creek, since their only crop is grass), keeping soil covered and integrating livestock.

This focus on context means they also find ways to make every component of the system work to benefit other components. “For example, instead of us going out to spread seed ourselves,” Meagan said, “the cows are out there eating it, pooping it, planting it, doing the job for us naturally. It takes time and labor away from us.”

All in all, Barney Creek’s main goal is to “give more back to the land than we take” and do the best they can to help mitigate climate change in the process. “If we’re not on the train to fight climate change, our kids will not have the same life we do,” Meagan said. “They will be making meat in a lab. And that’s gross.”

“Of course, you don’t need to eat meat,” she added, “and I tell VISIONS kids that all the time. But you do need to know and understand that grazing animals like cows have a place in the ecosystem. You also need to understand the impact of the food you do eat.”

In short, just because it’s a vegetable or fruit doesn’t mean it is not produced in a harmful system. “Are your vegetables regenerative? Go eat the Impossible Burger, sure, but I challenge you to know what’s in it. How is it made? Is it contributing to regenerative ecosystems, or is it promoting monoculture?”

Regeneration, Not Sustainability

Sustainability is a major buzzword in the modern environmental lexicon, but Meagan actually doesn’t use it, at least not to describe Barney Creek.

“We don’t like to use that word. You can have a crappy system and now you’re just ‘sustaining’ it,” she said. “We regenerate here. We adapt, change and shift. There’s nothing wrong with sustainability, but when we’re talking about a system, we don’t want to ‘sustain’ a system. We want to constantly work within that system, regenerating and changing it and helping it grow.”

The idea of regenerative agriculture goes beyond the environment, too. It also concerns fiscal viability. An eco-friendly system that doesn’t allow the farmers to make an income won’t work for long. “We have to make sure these techniques are profitable, too,” she added.

Meagan and Pete recently visited an in-person talk by Paul Hawken, author of Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reverse Global Warming. Both were extremely impressed.

“Some of my friends say, ‘We can’t let General Mills or Walmart control this conversation.’ But at the same time, they have all the money,” Meagan noted. When she raised this question to Hawken at the talk, his response impressed her immensely.

“He said, ‘Hey, those big corporations are willing to support this right now, so you come up with good projects, get them to fund it, do what you can do to shift the narrative.’”

In a sense, you don’t fold. There’s too much on the line to quit. You play with the cards you’re dealt.

That’s another reason why Meagan sees the term “regenerative” as so much more empowering than sustainable. Sustainability sounds like doggy paddling, struggling to keep from sinking under the tide. Regeneration sounds like fighting back. Climbing up out of the flood and making a difference.

“We don’t want people feeling helpless,” she said. “When all you hear is fear and doom and gloom, you’re just like ‘Screw it.’ We want to teach them what we can do to take action. We can regenerate. We can do this.”

Empowering the Youth

Meagan is a big believer in the profound impact today’s youth can have on tomorrow, which is one reason why she finds her work with VISIONS so inspiring.

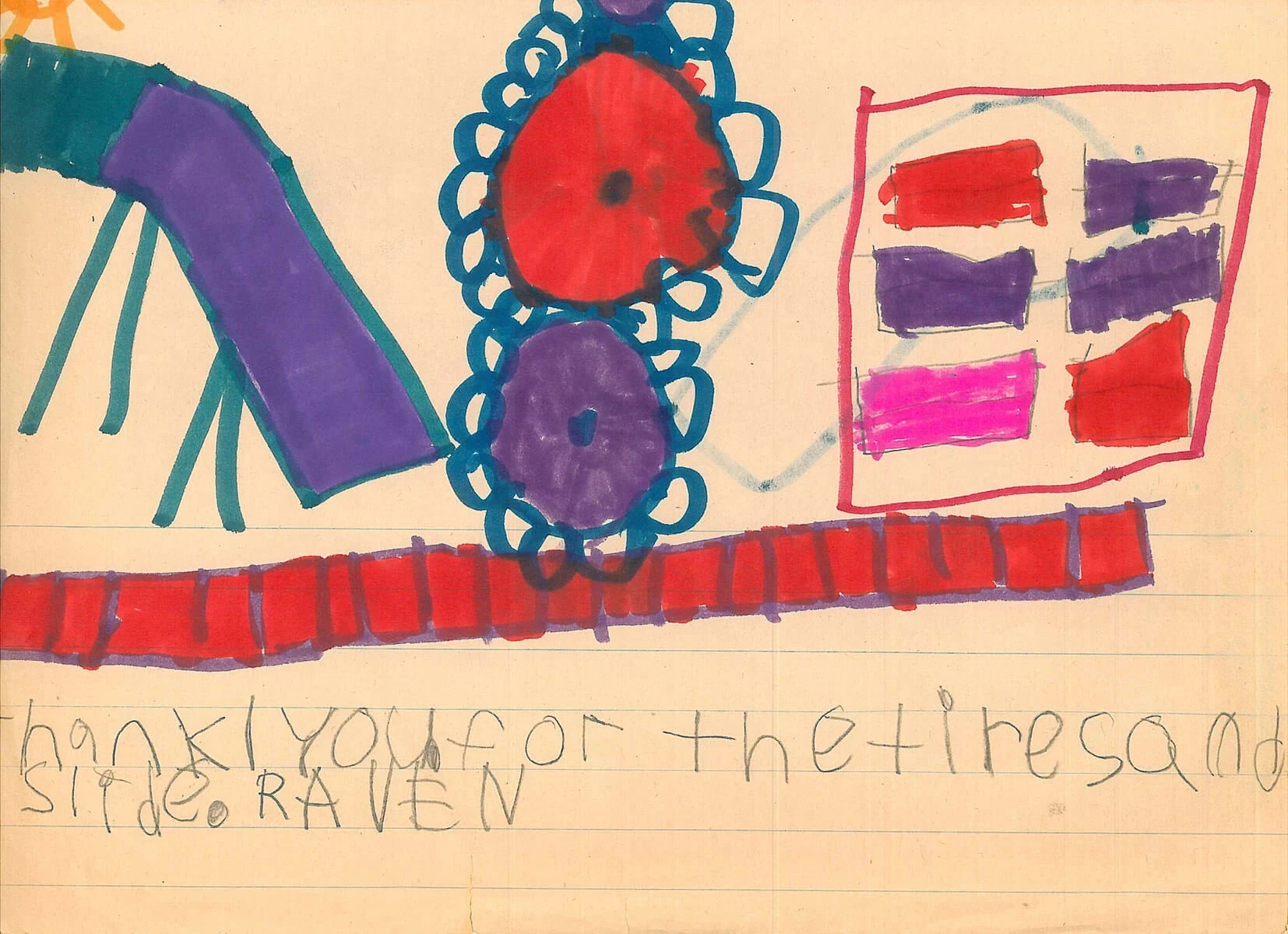

The proof is right in front of her at home, too. Her daughter, Maloi, created her own coloring book, Don’t Call It Dirt, at the age of 11. The book uses a cartoon character, Barney McQuack, to teach elementary school kids about the importance of regenerative agriculture. Maloi managed to secure a grant for funding write and publish the book, and wrote to a variety of regenerative agricultural figures, such as Gabe Brown, Joel Salatin and Nicole Masters for support. Almost all of them wrote Maloi back, providing encouragement, quotes for the book and other aid. Now Maloi sells her coloring book for $10, using the money to buy sheep for the Barney Creek farm.

Maloi is a perfect example that age is no object. It doesn’t matter if you’re a kid. It also doesn’t matter if you live in New York City or L.A. or a small town in Montana. It doesn’t matter whether your passion is regenerative agriculture or environmental architecture or river pollution.

“You can start your own project right now,” Meagan said, “and it can have a real impact. It doesn’t have to be agriculture, it can be whatever you’re passionate about. You can get the word out now. You don’t need to be out of high school, out of college, to start making a difference.”

“We Couldn’t Do This Without VISIONS”

Meagan teaches VISIONS students about the processes of regenerative agriculture through a variety of workshops, but VISIONS students also play a crucial role at Barney Creek. Students help Meagan and her family with a variety of projects, from riparian stream restoration to fence building to tree planting to meatpacking.

But VISIONS doesn’t just help Barney Creek with physical labor. “We’re learning from VISIONS kids just as much as they’re learning from us,” Meagan said. “Working with VISIONS puts us back into the mindset of, ‘Why are we doing this work in the first place?’ Why is it important to remember the little things supporting a larger mission?’”

“They’re bringing passion and making short order of projects that would probably take us ages,” she added. “There have been some jobs they’ve helped us with that we’ve been trying to get to for three years. It might seem like meaningless labor, but it’s contributing to this huge picture [of regenerating an ecosystem]. When you come back through Livingston many years from now, you can stop by here and you will see these trees you planted, this fence, this riparian area, and you’ll be able to tell your family, ‘Hey, I built this!’”

“We could not do this without VISIONS being here.”

Barney Creek Livestock was recently featured in a documentary film, To Which We Belong, which “highlights farmers and ranchers leaving behind conventional practices that are no longer profitable or sustainable.” You can learn more about the film here or visit Barney Creek Livestock’s website here.