By Owen Clarke

Kareen Erbe, the owner of the permaculture company Broken Ground, has been involved with VISIONS in various capacities for years. She was a staff leader in Peru in 2005 and helped start our inaugural Mississippi program in 2006. She met her husband, Jason, during the former program, where he was serving as a program leader.

(Jason went on to create a short film, Mi Chacra, about the life of an indigenous Peruvian subsistence farmer and porter on the Inca Trail, which won awards around the world, including Grand Prize, at the Banff Mountain Film Festival. You can read more about the film HERE.)

Erbe’s stepson, Taylor, also participated in VISIONS programs, first in Ecuador, where he accompanied his father at the age of six, and later in Nicaragua at 17.

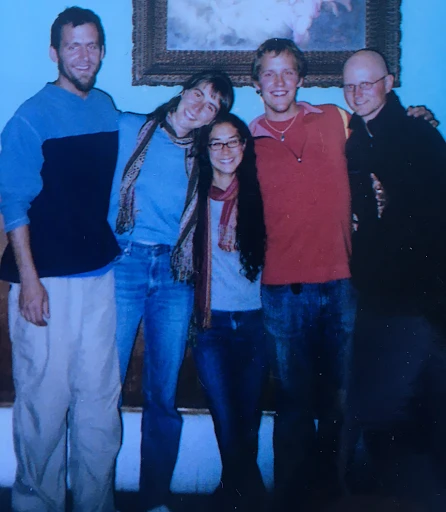

Kareen (middle) with Peru team.

Now-husband Jason is on left.

So, it’s safe to say that Erbe has lived the full VISIONS experience, on both sides of the aisle (as a leader and a parent).

Today, she lives in the Gallatin Valley (Bozeman, Montana—our homebase) and teaches a permaculture workshop to VISIONS participants during our Montana Farm & Ranch Program.

Activism or Action?

Born in Australia and raised in Alberta, Canada, to a Singaporean mother and an American father, Erbe’s upbringing was as diverse and multicultural as can be. “From an early age, I was in a bicultural, biracial family. My father was a mathematician, he had many graduate students from other countries,” she said, “and my mother and sister were both born in different countries, as well.”

It’s no surprise, then, that she gravitated towards international activism.

After earning her bachelor’s in environmental science from Queen’s University in Ontario, Erbe took a year to travel South and Central America while learning Spanish, eventually ending up in Guatemala. There, she worked as an activist in the country’s indigenous communities for the nonprofit NISGUA (Network in Solidarity with the People of Guatemala), following the country’s brutal civil war (1960-1996). Later, she worked with the Denver Justice and Peace Committee, after heading to the United States to pursue graduate school in Boulder.

Kareen in her greenhouse.

But after years of activism, Erbe began to feel burned out. The life wasn’t for her.

“Being an activist was all about being against someone or something,” she said. “I wanted to look for answers and solutions to some of our problems, rather than always declaring: ‘We’re doing this wrong, and this wrong and this wrong.’”

Activism is, of course, necessary, Erbe believes, but for her, it was a dead-end street. “We need the activists, and I’ve known people who are spectacular activists, fighting the good fight for 30 or 40 years, and they have the character to do that. But I didn’t,” she said.

“I was going to shrivel up into a messy ball of tears and anger if I continued down that road. We need young, fiery activists who are outraged like I was in my early 20s. But we also need people who are providing solutions, giving us ways we can feel hopeful and empowered.”

This frustration led her to travel to India where, in 2003, she took a course called “Gandhi and Globalization.” The course discussed how Gandhi’s philosophy could be used today as a tool for confronting economic globalization and the injustice inherent in that system.

“Gandhi’s philosophy in his fight for independence against the British was all about localizing,” she said. “Relocalizing economies so they weren’t as dependent on the British.” The course was about how that same philosophy could be applied to other fights for justice in the modern world.

This was when Erbe first heard the word permaculture, a practice Erbe calls the “art of cultivating beneficial relationships.”

The practice would go on to define much of the second half of her life.

What is Permaculture?

The study of permaculture allows us to learn how to live more sustainably, in harmony with the land, flora and fauna around us. A complex definition of the term than cultivating beneficial relationships, Erbe said, is “a design approach for sustainable living and land use that is rooted in the observation of natural systems.”

The real key to permaculture, however, is learning to look at landscapes and lifestyles in an integrated way and connecting ourselves to the places we live. “We’ve become so disconnected in our society from where our food comes from,” said Erbe, “and permaculture is all about reconnecting people to place and giving them an understanding and appreciation of that.”

Permaculture isn’t just about becoming more self-reliant or sustainable on your own, either, but about elevating the ecosystem around you too, about improving life for all forms of life, plant, animal and human.

“If we have a surplus, we feed it back into the system,” Erbe said. “If you have a surplus of manure, you give it back to the earth. If you have a surplus of vegetables, you give them to your neighbor. If you have a surplus of time, you help someone in their garden.” This idea is part of what’s called “fair share,” one of three ethics of permaculture, which we’ll discuss below.

The Ethics of Permaculture

Earth Care, People Care and Fair Share are the

three “ethics,” or pillars, of permaculture.

- Earth Care is the idea of rebuilding natural capital. At a base level, it can be taken to mean looking after the living soil. The soil is where all life on the Earth begins and soil health is an excellent measure of societal health. Perhaps the simplest way to tell if the soil is healthy is simply to see how much life is living on it.

- People Care is the idea of looking after oneself, one’s kin and one’s community. This includes our families, neighbors and community at large. People care is all about growing via self-reliance and personal responsibility. To properly follow the people care ethic, we need to learn to focus on non-material well-being and take care of ourselves and others without consuming unnecessary material resources (or producing them).

- Fair Share is the idea of setting limits and redistributing surplus. Everyone encounters times of abundance and everyone encounters times when resources run thin. It’s important to redistribute excess resources in the former times so that everyone can help survive the latter times. Besides, excess isn’t always good. Growth in human consumption (and production), has shown that continuous growth is an impossibility, and will lead to catastrophe for the planet if left unchecked. Fair share is all about learning your limits and redistributing surplus once you reach them to help lift up your community.

Our Permaculture Workshop

In Erbe’s workshop, VISIONS participants take part in several activities to understand the principles of permaculture and how they can be applied in day-to-day life, learning a variety of tools and strategies to foster

sustainable living in their own lives. They learn how these principles can be applied both on a large, “landscape-level” scale and in their own lives.

Later, as a final project for the workshop, participants design their own mock site on the VISIONS property using the principles of permaculture, taking into account efficient methods of food and water sourcing, minimizing carbon footprint, passive solar design, greenhouse placement and more. When you join our Montana Farm & Ranch Program and participate in the permaculture workshop, you’ll be given the opportunity to put your permaculture skills to the test!

Bringing Permaculture into YOUR Home

Of course, it’s one thing to be connected to the land while living on the VISIONS farm in Montana. It’s another to be able to apply those principles when you’re back home in Seattle or Atlanta or Los Angeles.

The great thing about permaculture is that you can practice it anywhere. You don’t need to live in a hut in the forest. Erbe’s workshop teaches practices that can be adapted and applied in a variety of living situations, from urban to suburban to rural.

“[Permaculture] is an invitation to connect to the natural world and your place, wherever you live,” she said. “It’s relevant across the world, in all home settings and lifestyles. Maybe you don’t have space for a 500-square-foot garden at home, sure, but you can grow herbs in a pot, for example. You can always take steps to make your life more sustainable.”

It’s easy to get overwhelmed with everything going on in the world today with the climate crisis, but one of the best things about permaculture, according to Erbe, “is that it gives you the tools and strategies to work towards a positive, solution-focused goal.”

During her work in the nonprofit sector, Erbe often spoke in high schools, teaching high schoolers about economic globalization and the social and economic justice issues facing the world today. “A lot of high school students would tell me, ‘Yeah, this whole situation in the world sucks, but what do we do about it?’” she said.

“And that’s what’s so powerful about permaculture. It’s all about letting people know, ‘You can take these steps to fight back, and it will make a difference.’”

“What do we do as individuals, privileged people, to make a difference, to respond? Permaculture is a solution to that. By relocalizing our economies, we can have an impact.

Not only is the global food system unjust to the poorest of the poor in foreign nations, but it has a massive carbon footprint. Permaculture fights that.”

When you complete Erbe’s permaculture workshop, you’ll come away with the knowledge that you can have a positive impact on the world and that your actions do matter, even if you’re acting alone or with a small group of friends or family. Everyone can make a difference, and permaculture doesn’t just remind us of this and prove that it’s true. It also shows us exactly how it works.

Finding Lasting Solutions

Following her course in India, Erbe passionately began studying the art of permaculture. She earned a Permaculture Design Certificate in 2006 at the Taranaki Environment Centre in New Zealand and finished an advanced permaculture program at the Permaculture Research Institute of Australia. The was later trained in teaching permaculture by Rosemary Morrow, the author of what many consider the permaculture bible, Earth User’s Guide to Permaculture.

She has volunteered on farms from China to Australia to Massachusetts, in addition to extensive work in the Bozeman area, which she now calls home.

Today, Erbe works through her business, Broken Ground Permaculture, to teach people how to grow their own gardens, capture moisture, layout their yards, and make their lives more sustainable all-around via permaculture practices. She has clients from Texas to Colorado to New Mexico to Canada and even further afield through online workshops, but most of her work is local, in the Gallatin Valley.

Social Capital

The idea that there are eight forms of capital can be attributed to Ethan C Roland and Gregory Landau, who first postulated this view in 2011, in an article you can read here. Capital is not just financial, as we in our capitalist Western society tend to think, but material, natural, intellectual, experiential, spiritual, cultural and social capital.

The latter, which is defined as the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively, is a key part of permaculture. In short, creating community.

“This goes back to that principle of fair share,” she said. “Some people in the community can pay for my services, and this allows me to volunteer my time free of charge to help others via these potlucks and other events.”

Trust Your Gut

In the modern world of social media activism, it can be easy to feel like you’re doing something simply posting a black box in honor of Black lives or retweeting a nonprofit’s Earth Day post… When in reality you’re just spinning your wheels.

On the flip side, this realization can lead to a feeling of hopelessness and futility, which is neither warranted nor productive.

Sure, it can be hard to feel like you’re able to make a difference when you’re stuck in a consumer-driven urban haven like Manhattan or Atlanta or Los Angeles, unable to own your own land or grow your own food (Hint: You actually can!).

But permaculture teaches us that we CAN make a tangible difference, with our own hands, in the communities we live in, wherever they are.

But although Erbe found direct action through permaculture a more sustainable and productive method of for teens today than the activism she was practicing in her early 20s, she believes activism and action are equally important.

What’s most important of all, however, is trusting yourself.

“As long as you’re doing something you really want to do,” she said. “That’s what matters. Don’t do what everyone else is doing. Don’t just do what your parents, or your teachers, or your peers would be proud of you for doing.”

“Whatever in your gut feels like the biggest expression of who you are, that helps you make a difference… Well, that’s what you should do.”